At this week’s Rewired 23 conference, our CEO, Thomas Webb, shared Ethical Healthcare’s research into EPR usability.

Here, he summarises the findings and why he believes implementation is more important than functionality when it comes to long-term clinical engagement.

The research

In 2021-22, Ethical Healthcare, in partnership with NHS England and KLAS Research, delivered some national-level surveys on the usability of EPRs across acute, community, mental health and ambulance settings.

We got over 10,000 responses which, as far as I know, is still the largest usability research ever undertaken.

It was no mean feat, and a brave thing for NHSE to do, knowing that the results wouldn’t necessarily be good and that they would be public. In particular, NHSE are really nailing it by surveying digital maturity (i.e. EPR functionality) alongside usability through the What Good Looks Like framework. Neither usability nor functionality provides the full picture on their own, but together they are really powerful.

Results and key themes

The results of the survey completely supported the macro-level findings of KLAS across all data sets. That is that 66% of variation in usability is down to the provider, not the system or supplier. Or in layperson’s terms; it’s less the system, it’s more what you do with it.

This perhaps sticks in the throat a little, given that in the UK many clinicians have dim views of their systems and suppliers, nonetheless it’s what the data shows.

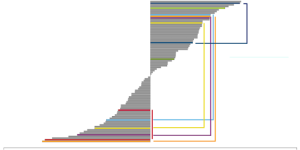

The graph below illustrates the variation in usability for single systems, shown by the brackets. As you can see, these same systems can vary wildly in their usability. But, what is happening here? Why do some Trusts love a system while another is ‘meh’ or worse?

Luckily the answers to this are clear.

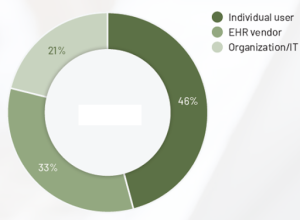

What this is telling us is that yes, 33% of usability is down to the supplier and their system – mainly, how interoperable and configurable it is, the user interface itself. But the rest is down to two main areas:

1. The individual user’s capabilities and knowledge of the system.

2. The overarching clinical engagement and whether the system is owned and designed by clinicians.

Delving into the details of this, we discovered where the NHS was particularly struggling:

1. Training

Even the top five training Trusts in the country were still in the bottom 50% of providers globally. Training levels in the NHS are relatively very poor. There was a clear link between those users who wanted more training and their usability ratings. A key lesson to be hardwired into the NHS is that training is constant and continual. It is not a one-off or discrete event that takes place at go-live or induction. Every day is a school day.

2. Infrastructure

Poor infrastructure is really harming usability. Infrastructure includes hardware, everything from a slow network and five-minute login times to broken keyboards, mice and computers.

This is foundational; you can have the best system in the world, but if you run it on rubbish kit, you’ll hobble it. The NHS has far to go in improving system response times.

3. Clinical engagement

We are pretty rubbish at doing the hearts and minds stuff well. The NHS would need to double its scores here just to be average at it. These are not systems configured by clinicians for clinicians. At the moment, the user body feels ‘done to’ by IT – the feeling of ‘them and us’ still pervades. This is a hard problem to solve but it’s been tackled by other health and care systems, so it can be done.

Implementation over functionality

So, what does this all mean?

Well, there is an interesting overarching point here. The first graphic shows that implemented well, pretty much any system can beat another system for usability. So, the differentiator, the thing that is going to make a difference, isn’t the system. It’s you. It’s how you’re going to implement it and optimise it.

And yet, nearly every EPR programme spends HUGE amounts of time pouring over evaluating the functionality of a given system. The ratio between quality and cost in the procurement. The requirements themselves. Hours and hours and hours spent. Consultants brought in (including us!). Trusts will spend huge amounts of money on the systems themselves, but in the business cases I’ve seen, about a third or half as much on the implementation team.

We are actively choosing to spend less on the most important bit! We divert attention to the relatively easy and interesting bit of choosing a new toy to play with, and away from the wicked question of addressing our own organisation’s ability to actually use the thing. Business cases also seem to end about six months after implementation, as though that’s it done. No ongoing training funded, no ongoing clinical engagement. And digital teams wonder why clinicians are all so disengaged.

So, in summary, stop obsessing over the choice of system. They are largely much of a muchness – done well, you can make nearly all of them sing. Instead, focus on and fund the things that matter: your own organisation’s capabilities. In particular, training, infrastructure and clinical engagement.

As a footnote, all of this is not to say that suppliers don’t have a mountain to climb in terms of their usability. Some of these systems look like they were designed in the 1990s (they were). But the data shows that you can still make these systems work, and work well. The evidence is there. We all just need to start using it.